It’s hard to have any discussion about the Sudbury region’s industrial base without an extensive discourse on the mining industry. Sudbury is well known for being one of the world’s major sources for the production and refining of nickel, and the largest mining and smelting company in the area was the International Nickel Company, or INCO (today owned by Brazil’s Vale). Other companies in the area such as Canadian Copper Company, British-American Nickel Co. (BANC), and Mond Nickel were absorbed by INCO in the early 20th century helping to make INCO the biggest player in the Sudbury region.

INCO operated a large smelting and refining complex west of Sudbury at Copper Cliff, expanded from and replaced the original Canadian Copper Co. smelter in this area. Another older smelter at Coniston, built by Mond Nickel in 1913 was at the end of its useful life in the 1960s and finally closed in 1972. From the late 1970s to 2010s ore from all of INCOs mines was processed at the Clarabelle Mill, which opened in 1971 to consolidate all ore processing at a single mill.

INCO operated several large mining operations in the area, most of which were served by rail, and this posting will survey the mine and ore train operations of the 1970s which are (or will be) represented on the WRMRC’s layout.

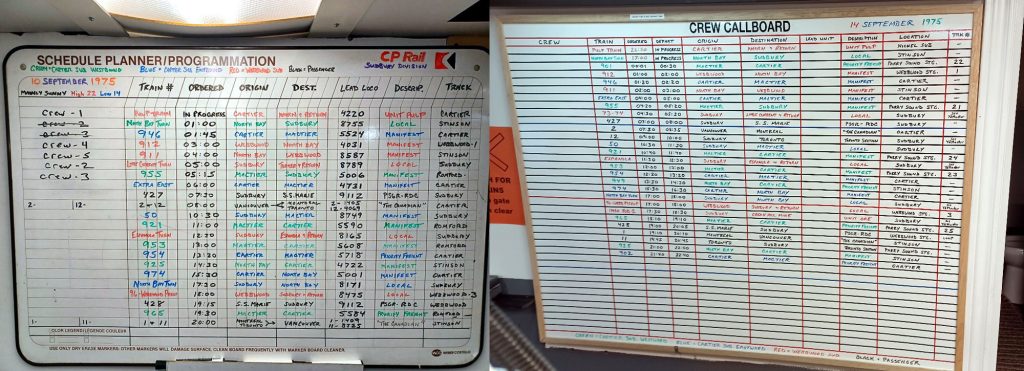

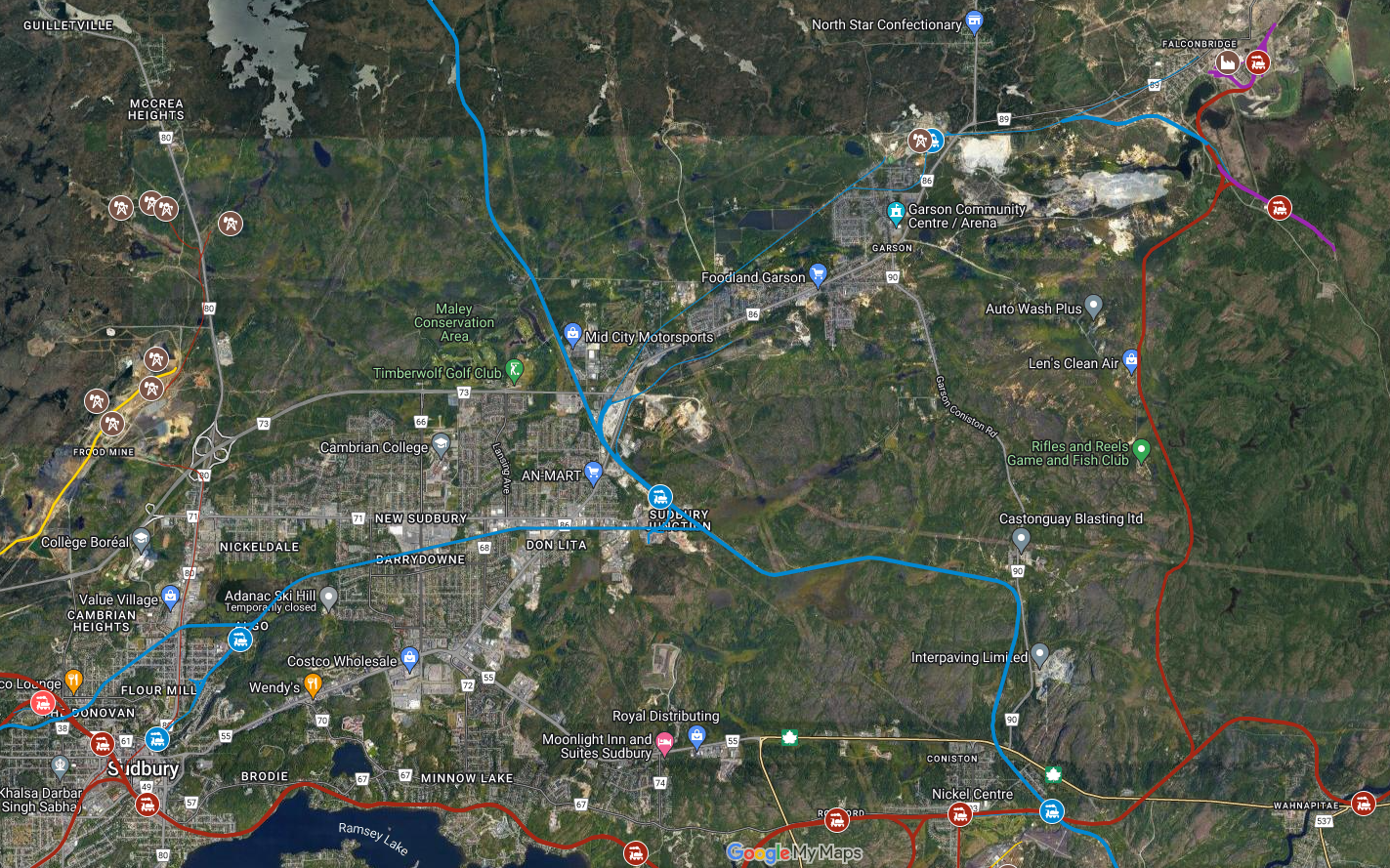

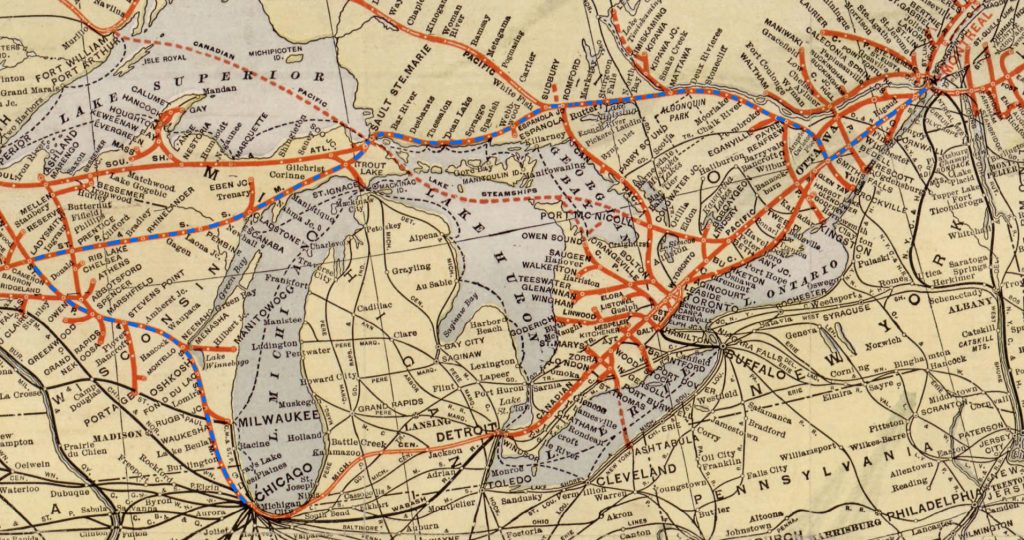

Map of INCO mines and interchanges on WRMRC’s modeled territory. Mines are highlighted in blue, and CP-INCO interchange locations in green. Crushed quartz was also shipped from Lawson Quarry (highlighted in yellow) to Clarabelle in modified ore cars.

The key map above represents the Sudbury Division as modeled by the WRMRC. CP-served mines are highlighted in blue, and the interchanges connecting to INCO’s railway operations at Copper Cliff are marked in green.

In the 1970s, CP ran three unit ore train assignments for INCO. These were known as “INCO-1” (Creighton Mine), “INCO-2” (Crean Hill Mine), and “INCO-3” (Levack Mine). This posting will act as an overview of these operations and the mines they served.

Note: For a survey of the cars that CP used in ore service see the previous blog post The Sudbury Ore Car Fleet

INCO-1 (Creighton Mine to Clarabelle)

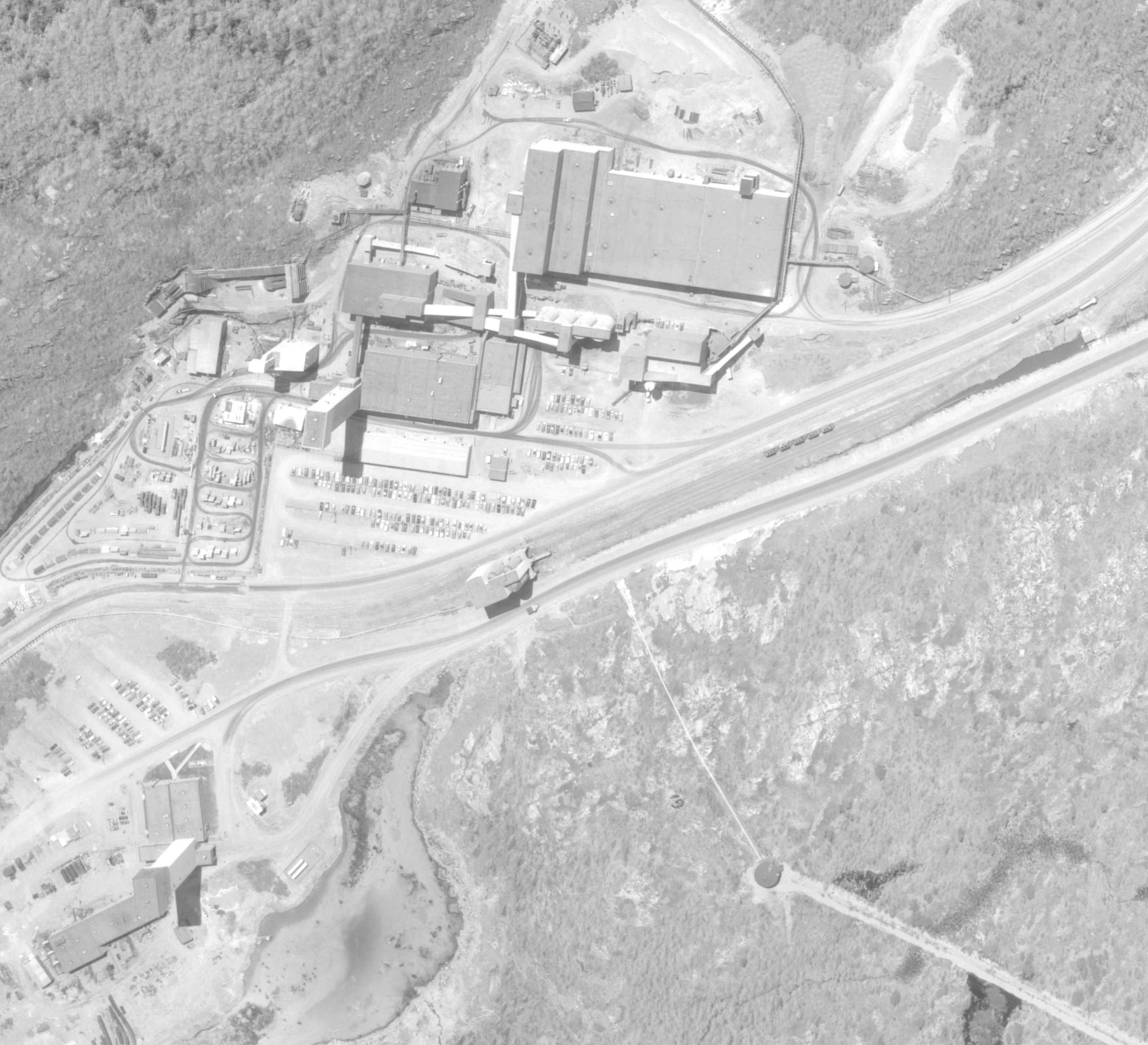

Creighton Mine, 1970. John Brown photo, WRMRC collection.

Creighton Mine is still active, and one of the oldest currently operating mines in the country, and while served by a CPKC line, is located so deep in Vale INCO private property and away from public roads that these trains are not easily seen.

Fans of astronomy and astrophysics will also note Creighton Mine as being the location of SNOLAB, the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory/Detector built deep underground in a cavern connected to and accessed via the Creighton Mine shaft system.

Train symbol INCO-1 would have been based out of Sudbury yard, running as a caboose hop on the Nickel Subdivision to Clarabelle where empty ore cars would be lifted from the INCO interchange yard, then on to the end of the line at Creighton to switch out loads and empties at the mine shafts. Then the train would head back for Sudbury, shoving the loads into the INCO interchange at Clarabelle on the way back.

While the Creighton Mine is still active today, as mentioned, there have been many changes over the years and in the 1970s the old No. 3 and 5 shafts would have still been active, while today the modern No. 9 shaft is the main access and the older shafts are abandoned and capped with the associated structures demolished, so the track arrangements around Creighton are quite different today.

INCO-2 (Crean Hill Mine to Clarabelle)

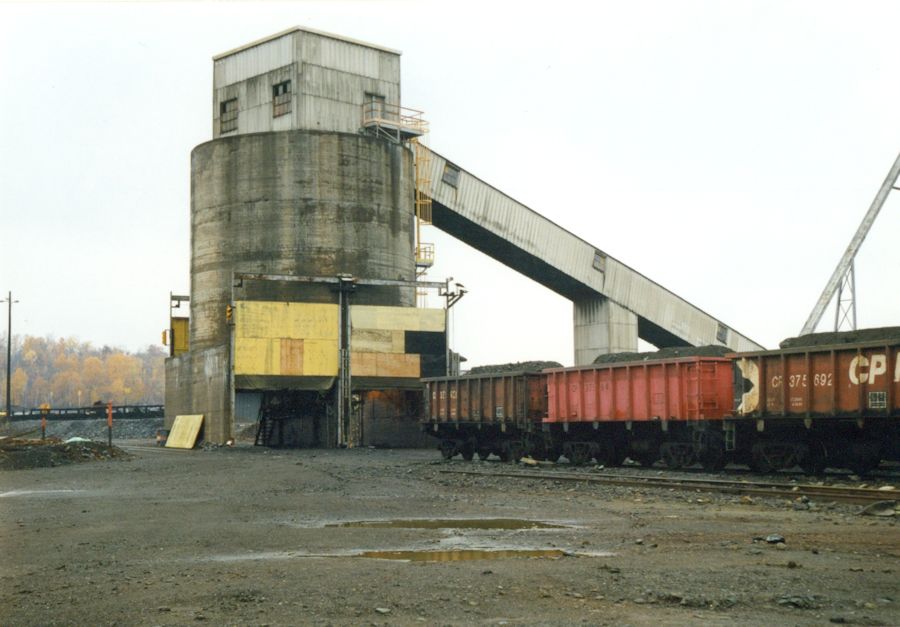

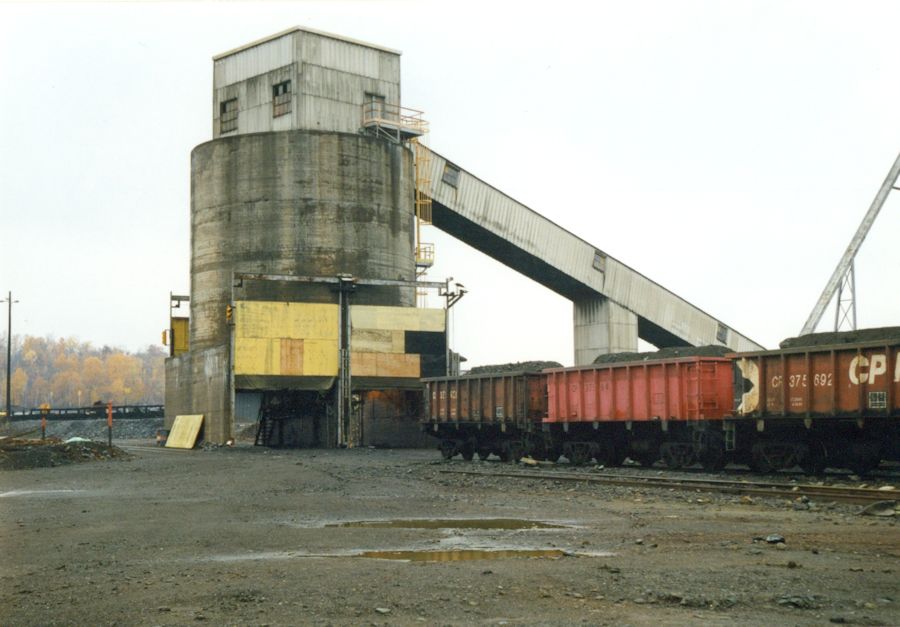

Crean Hill Mine in the late 1990s. WRMRC collection.

The second INCO ore job serviced the Crean Hill Mine west of Sudbury on the CP’s Sault branch. This mine was accessed via the “Victoria Mine Spur” which connected to the Webbwood Subdivision at Victoria Mine. Why the different names? Well in the early 20th century CP had a previous station at or near the same location where the spur connected to the main line called Victoria Mine, which served a Mond Nickel mine of the same name. So the railway location and spur inherited the historical name.

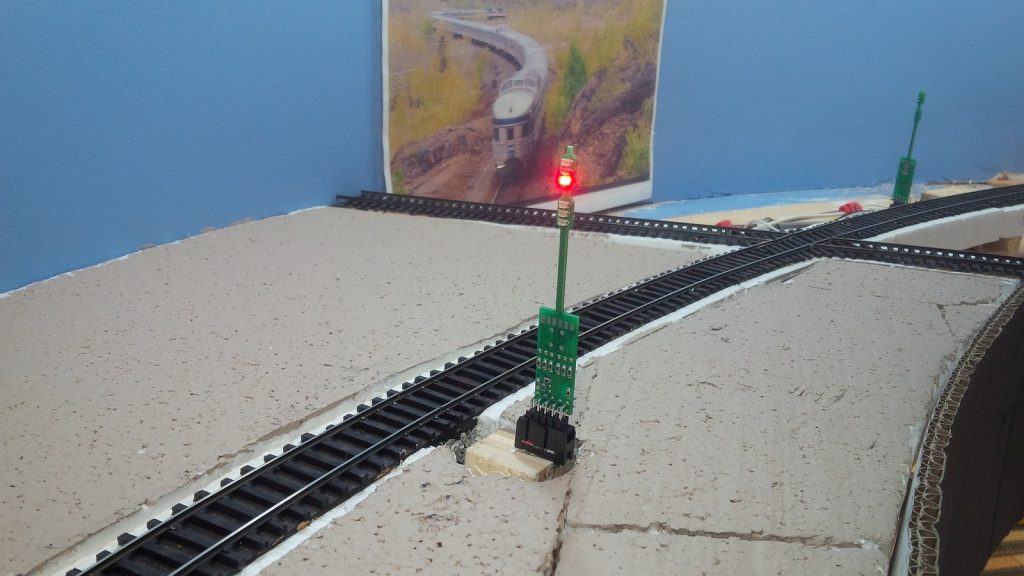

The Victoria Mine Spur/Crean Hill Mine is the first of the INCO nickel mines and ore trains to be built and placed into operation on the WRMRC layout, with 3D printing technology enabling us to finally build and place into service a train of accurately modeled ore cars.

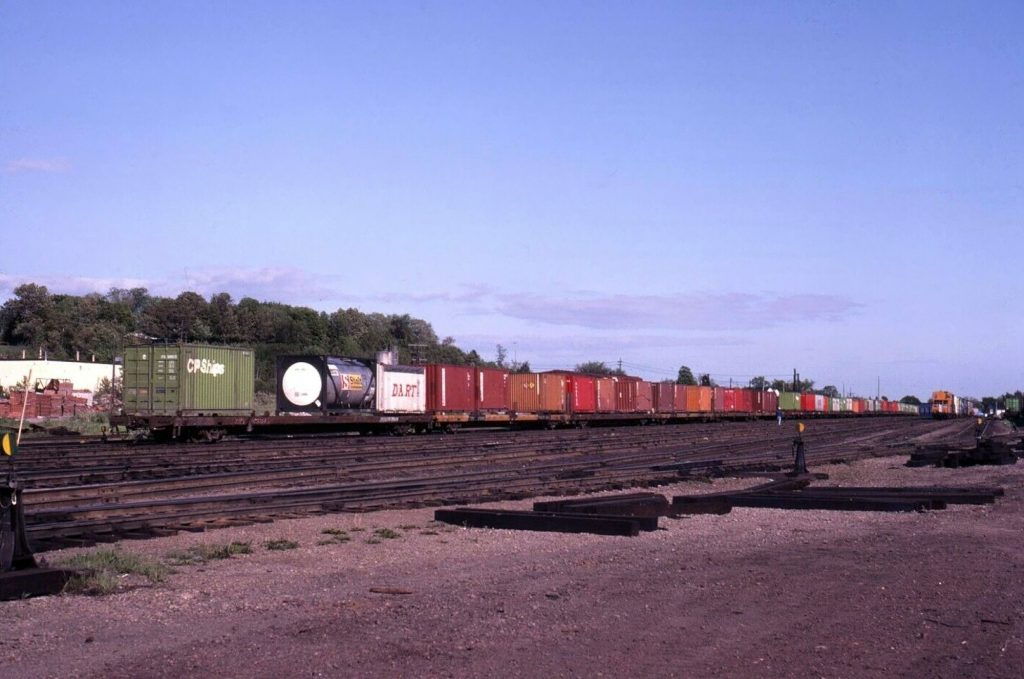

Ore train at Crean Hill Mine on the WRMRC layout.

A second mine, INCO’s Totten Mine at Worthington, was also located on the Webbwood subdivision, however this mine was closed in 1972. Due to its short period of operation relative to our modeled era, space constraints, and the fact that we already had one other mine on this line, this location was excluded from our model layout. (Interestingly, this mine was redeveloped in the mid 2000s, however ores are today shipped to Clarabelle Mill by truck, not rail.)

Abandoned loading conveyor at Totten Mine (Worthington) in the late 1990s. WRMRC collection.

Train symbol INCO-2 would have again been based out of Sudbury yard, running up to the Victoria Mine Spur on the Webbwood Subdivision to swap empties for loads at Crean Hill Mine, then back to Sudbury to runaround and head onto the Nickel Subdivision to Clarabelle to deliver the loads to INCO and pull empties for the next run.

Crean Hill Mine was closed in the mid 2000s, ending this service, although currently there is a mining company exploring redevelopment of the Crean Hill Mine property..

INCO-3 (Levack Mine to Sprecher)

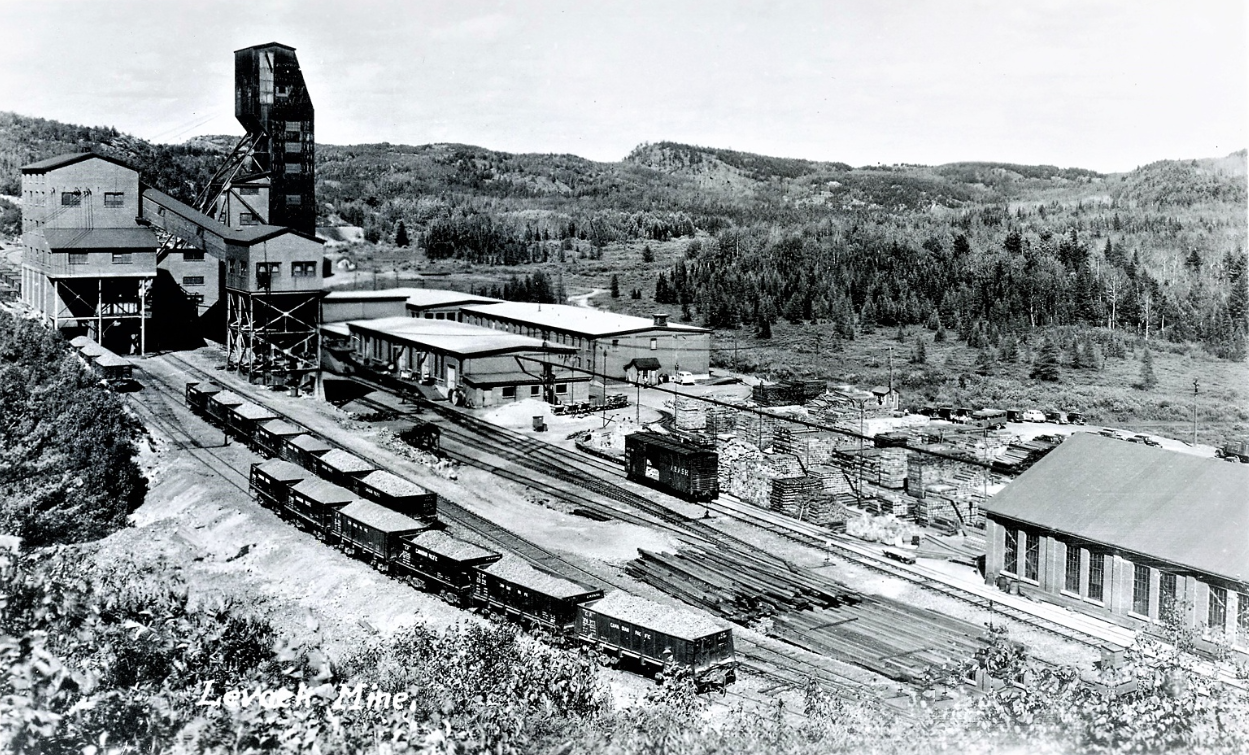

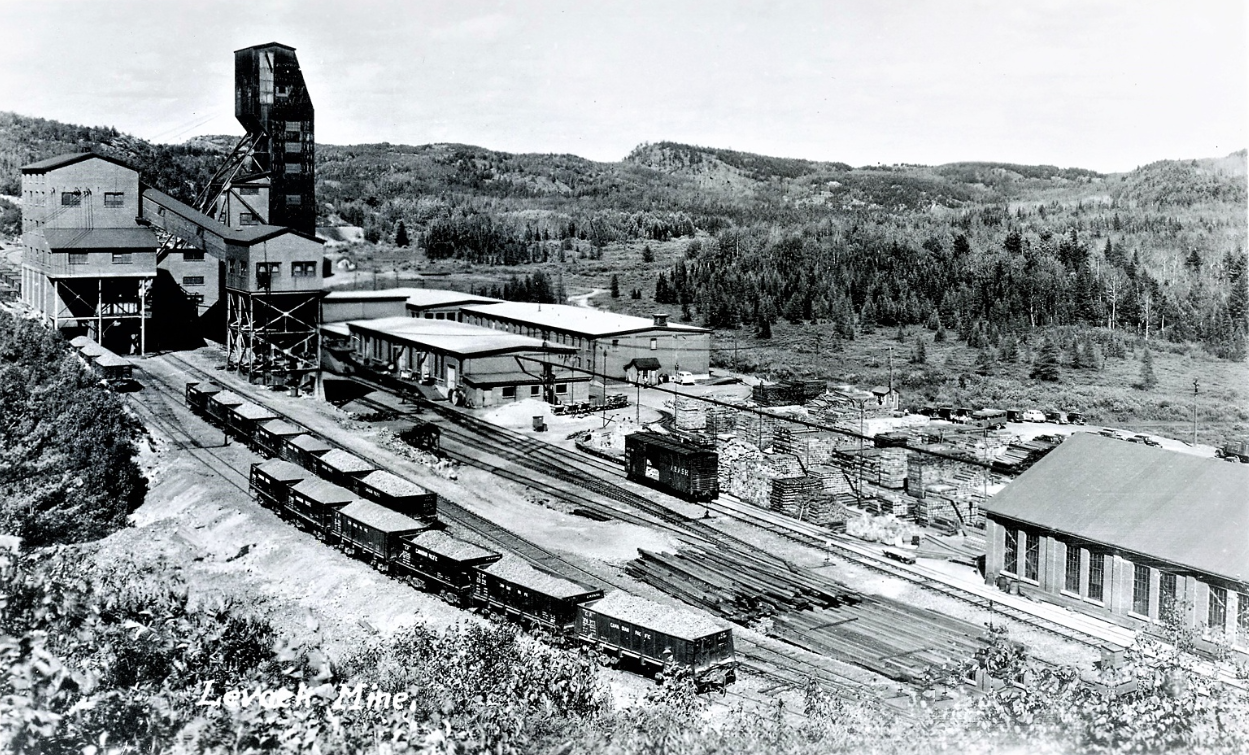

1950s view of Levack mine.

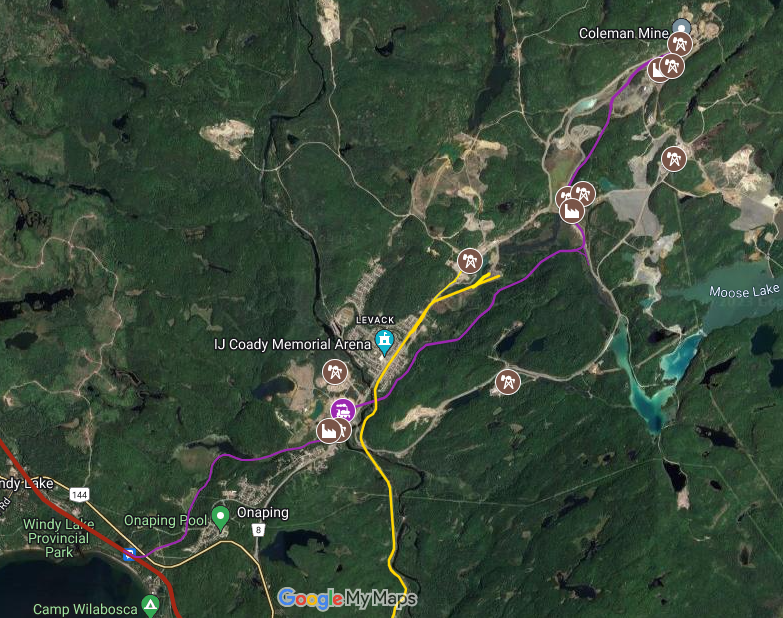

This job would operate out of Sudbury yard and lift empty ore cars from the CP-INCO interchange tracks at Sprecher, on the Cartier subdivision main track west of Sudbury. Having lifted the empties, the ore train would then operate over the Cartier subdivision west to Levack siding, where the empties would be exchanged for loads on a series of interchange tracks with INCO’s spur line to Levack. Like most of INCO’s operations, this line was operated with electric engines under trolley wire catenary, which would bring the loads down from the mine to the interchange at the CP siding, and then spot the delivered empties up at the mine.

INCO 100T electric #126 at Levack in 1970. John Brown photo, WRMRC collection.

Today CPKC still runs ore trains to Levack, although the old fleet of CP drop bottom ore gondolas have been retired since the late 2000s, and the ore is coming not from the same Levack Mine, but nearby Coleman Mine. Vale INCO now owns their own fleet of 220 modern ore gondolas built by Freightcar America in 2008, replacing both CP cars and INCO’s own previous fleet of aging cars. INCO’s old electric operations have long been abandoned, and CP locomotives handle the ore train all the way to the loadout tracks and do the switching themselves. While a few other mines are also still served direct by Vale INCO, this is the only ore train operating out on a CPKC main line.

CN Garson Ore

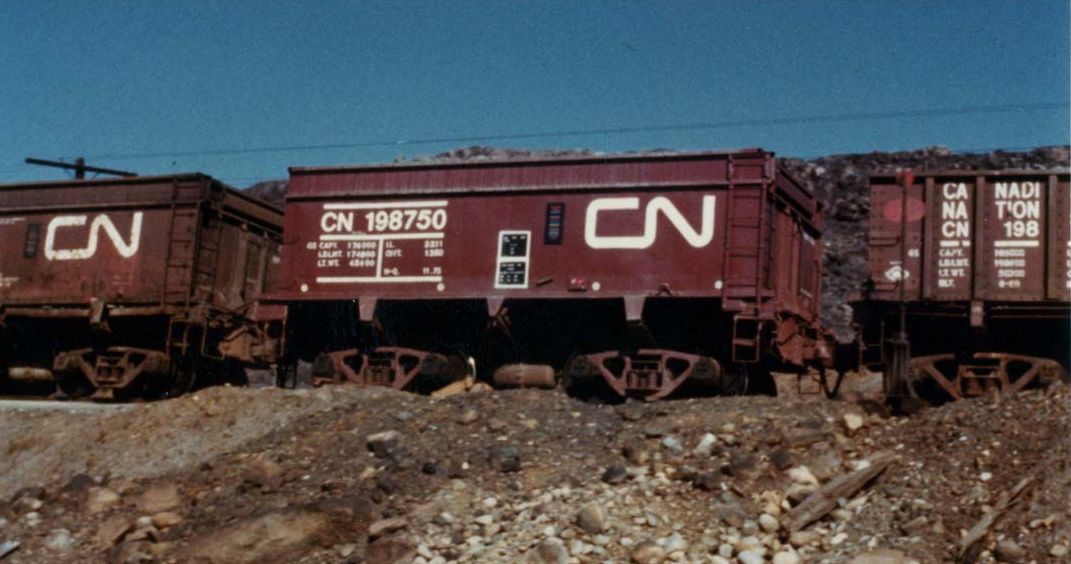

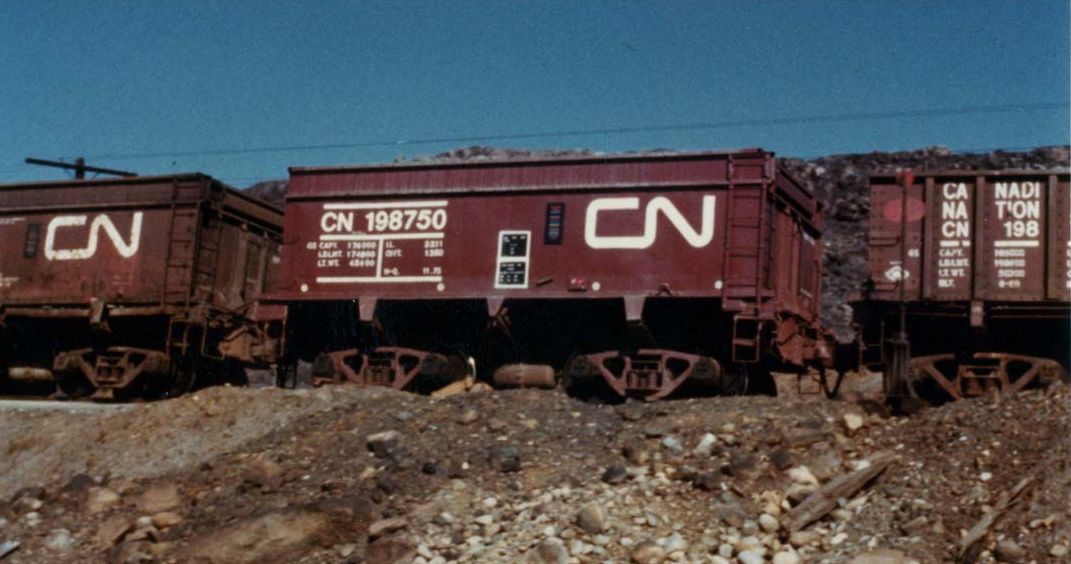

CN 198750. Bill Grandin collection.

Another source of ore for INCO was Garson Mine, located east of Sudbury between Sudbury and Falconbridge. This mine was served by a CN spur which accessed Garson Mine, a sand pit, and the Falconbridge smelter which will be discussed elsewhere. CN trains operating out of Algo yard in Sudbury would assemble a train of empty ore and sand cars, run out to the spur and switch the mine and sand pit, then run back across Sudbury to the CPR connection at CN Junction and joint trackage on the CPR Nickel Subdivision to interchange with INCO at Clarabelle to deliver the ore and sand to INCO’s operations. As CP did and does have exclusive physical access to INCO’s operations, all interchange traffic to INCO operated through Clarabelle, with CN sharing CPR tracks from CN Junction to Clarabelle and both railways jointly operating over this section.

Garson Mine appears to be still active today, but is no longer rail-served.

Other INCO Mines

INCO Copper Cliff South Mine in the late 1990s. The track at right next to the highway (Highway 55) with the stored cars is the CPR Copper Cliff Spur which accessed the INCO Iron Ore Recovery Plant, now closed. WRMRC collection

A few other INCO mines were rail served directly by INCO’s own private rail system connected to the Copper Cliff mill and smelter operations, and therefore would not impact CPR operations, although parts of these operations could be seen from CPR rails. These mines included Frood and Stobie, which were and are accessed via an INCO private line heading north from Clarabelle which crosses the CPR Nickel sub at grade at Clarabelle, and bridges over the Cartier sub near Sprecher. Copper Cliff South Mine is located alongside the CPR Copper Cliff spur near where it connects to the Webbwood Subdivision, and can actually be included on the layout as static non-operating tracks here. Frood and Copper Cliff South are still active, and served exclusively by Vale INCO’s private railway. There is also a Copper Cliff North mine, but being located immediately next to Clarabelle Mill it was not rail served.

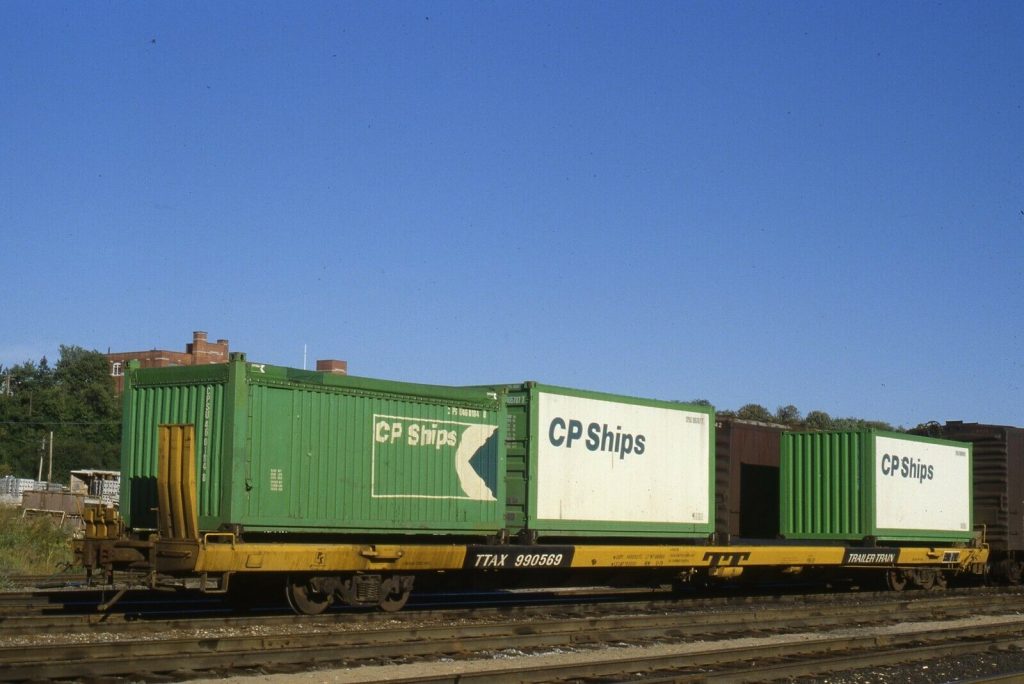

A loaded INCO train of ore returns to Clarabelle Mill from Frood/Stobie Mine. CP cars on the tracks in the background are loads from Levack on the Sprecher interchange track.

Lawson Quarry

An honourable mention, the quarry at Lawson Quarry south of Espanola on the CPR Little Current subdivision quarried crushed quartzite rock which was shipped to INCO to use as a flux in their smelting process. While not an ore-bearing rock, the quartz was shipped in modified ore cars with side extensions (as the quartz was lighter than the nickel ores) from the quarry to the INCO interchange at Clarabelle. The INCO quarry operation began in 1942, and rail operation ended by the early 1980s, although a quarry is still active here today.

Abandoned crushing/screening building and loading tipple at Lawson Quarry, late 1990s. WRMRC collection

While we don’t have solid information on the frequency of this operation, there is some indication that this was shipped in occasional “stone train” extras. We don’t have solid information on how often these trains operated, or any evidence on whether individual cars of quartz were occasionally handled by the regular trains 73/74 on the Little Current branch, although the limited information does point towards dedicated extra trains. Any further information or clarifications (on any of the topics and articles we post) are always appreciated.